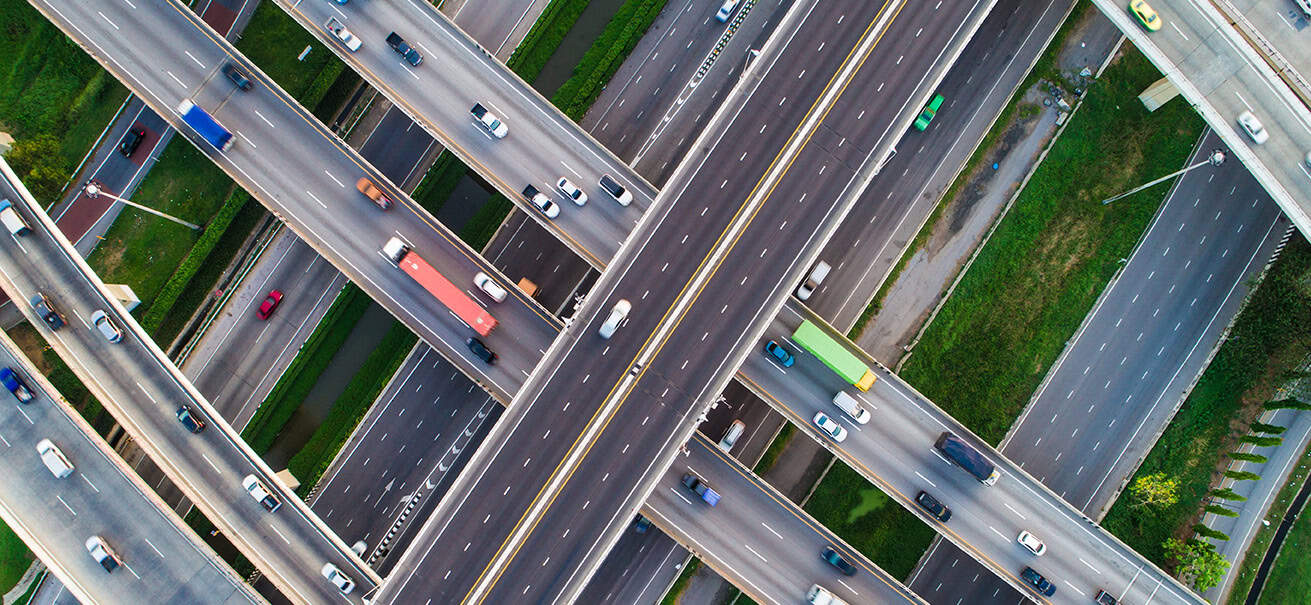

These days, virtually every media cycle brings news that yet another company has made a net-zero pledge, or that yet another regulatory body is considering action to curb climate impacts. We have known for a long time that supply chains account for much of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In fact, according to Boston Consulting Group, 50% come from the supply chains of just eight industries: food, construction, fashion, fast-moving consumer goods, electronics, auto, professional services and transportation. This figure is truly staggering. Yet if every large organization curbed its direct GHG emissions, what impact would that have? The surprising answer is—not much. How can this be, and what are regulators planning to do about it?

The Tip of the Iceberg

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol developed by the World Resources Institute breaks carbon emissions into three categories, or “scopes,” for reporting purposes. Scopes 1 and 2 include those the company can control, such as the emissions tied to company facilities and fleets. If GHGs were an iceberg, Scopes 1 and 2 would be just the tip for most companies, yet these emissions are often the ones companies include in their sustainability disclosures. Why? They are the emissions an organization can control—and they are also much easier to measure.

Scope 3 is something else entirely. It includes emissions from the sourcing, manufacture, transportation, end-use and disposal of all of a company’s goods This means they’re the bulk of the iceberg that lies below the surface on the route to net zero. According to a recent assessment of 25 of the world’s leading enterprises across industries, an average of 87% of emissions fell into Scope 3. The assessment also found that, despite net-zero commitments, few of these companies have formed an achievable plan to address Scope 3 emissions.

Why are Scope 3 emissions so hard to address? It’s because we live in a world of outsourced mass production. Corporate decisions set actions in motion across potentially thousands of extended partners, driving climate impacts far beyond what the company can directly measure or control. This means that GHG emissions are by definition a multi-enterprise challenge. Measuring, reporting or even mitigating emissions for Scopes 1 and 2 just doesn’t move the needle much toward net zero. It now appears that regulators and investors on both sides of the Atlantic agree.

New Rules on the Way

New rules proposed in the United States and the European Union would require companies to significantly measure and disclose their Scope 3 emissions. At a minimum, this would involve mapping the bulk of the value chain—including all tiers of supply, outsourced manufacturing, co-packing, transportation, storage, distribution, use and disposal—and gathering emissions-related data from each participant. Let’s take a closer look at these proposals.

EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive

Financial performance has always been considered material information to investors. The EU and an increasing number of investors now recognize a principle called “double materiality.” This is the idea that sustainability information, not just financial data, is also material from an investment point of view and should be reported publicly—especially if companies are making public claims about sustainability. The EU already requires certain companies, primarily large investment and banking firms that control the flow of capital through Europe, to report on the environmental impact of their investments. This puts pressure on companies that are seeking to borrow capital to provide detailed reporting about the sustainability of their operations.

In a move urged by EU financial and investment institutions, in April 2021 the European Commission, the EU’s governing body, proposed a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This proposal would expand the existing reporting requirements laid out in the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which entered into force the month before.

Under the previous rule, only a handful of large investment capital firms had to report their sustainability data—including emissions. Under the new proposal, all large private European companies and all large companies listed on EU financial markets would have to report this data. The CSRD also seeks to standardize how companies report their emissions so that investors can make an effective apples-to-apples comparison between companies.

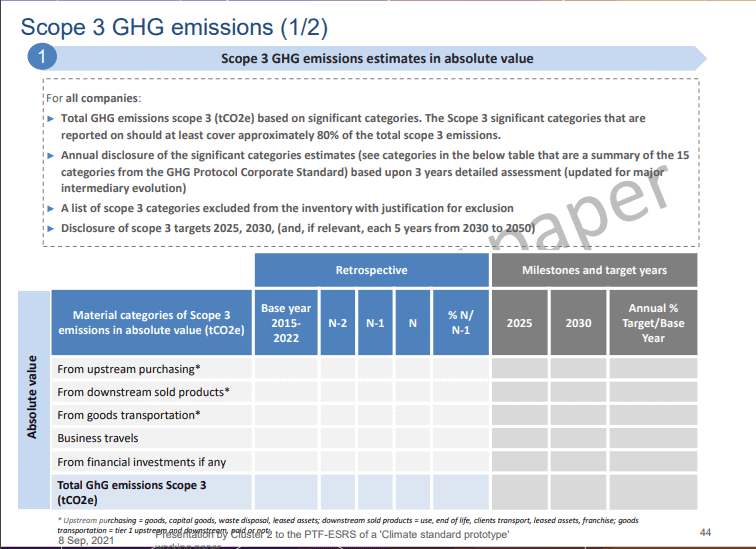

So, what exactly will companies have to report? This is where it gets more interesting. The European Commission has tasked the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) with developing the detailed guidelines, hoping to adopt them by October 2022. Climate leaders from the UN met in Scotland in September 2021 to discuss a range of issues at COP26, that year’s UN climate change conference. In conjunction with that event, the EFRAG developed a working paper to summarize the group’s current thinking and recommendations. As of this writing, as illustrated in the excerpt below from page 44 of the paper, the EFRAG plans to recommend that companies be required to report on at least 80% of their Scope 3 emissions. Though this working paper is not yet an official proposal, much less a law, it reveals how seriously EU regulators are taking Scope 3 emissions. Notably, the CSRD also includes required audits to help assure the accuracy and completeness of the data companies report.

New York “Fashion Act”

These moves by the EU put enormous pressure on US-based institutions and companies to take similar measures. In fact, legislators in New York State have introduced a bill called the “Fashion Sustainability and Social Responsibility Act” (“Fashion Act” for short). This new proposal would require manufacturers or sellers of apparel or footwear operating in the state to disclose their environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks within 12 months and their ESG impacts within 18 months. Specifically, it would require that they map at least 50% of their supply chain and disclose greenhouse gas emissions, wages, forced labor data and other drivers of ESG risk. They would also have to report their ESG goals, tactics for achieving them and how they plan to bring suppliers into alignment. Similar to the EU measure, the Fashion Act requires independent verification of the disclosures.

One of the most remarkable clauses of the New York proposal is that it would penalize companies up to 2% of gross revenues above $450 million for non-compliance. Since fines cannot be written off as a business expense, this could have a massive impact on net income. Take an apparel company with $4 billion in annual sales, 15% profit margins and net income of $600 million. Non-compliance with the Fashion Act would trigger a $71 million penalty, reducing net income by nearly 12%. Read that again—this is a double-digit impact on earnings.

Non-compliance would likely also diminish brand equity and increase the cost of capital, setting the company at a further disadvantage compared to peers that invested in supply chain mapping and ESG risk mitigation early on. This is enough to make Scope 3 emissions an immediate top priority for executives, board members and shareholders alike.

A Multi-Enterprise Challenge, by Definition

Because measuring Scope 3 emissions is by definition a multi-enterprise problem, few vendors can offer realistic solutions at the scale that the proposals would require. The most elegant and efficient way to map the supply chain would be to access an existing multi-enterprise network—such as e2open’s—that already spans each tier and ecosystem in a global supply chain: supply, logistics, global trade and demand.

This direct connectivity to upstream, downstream and logistics partners provides an efficient mechanism to capture ESG data and create a system of record (SOR) for reporting and compliance, and to evaluate the ESG impact of day-to-day decisions as those decisions are being made. That last phrase is important. This SOR should exist at the core of the business—not as an overlay—to empower companies to move the needle on ESG improvements across the whole value chain in near-real time, not simply to understand the ESG impact long after a decision was made.

Just like any other time the tidal wave of regulatory momentum began to build, companies that act early will be better positioned for compliance, competitive advantage and brand equity in the long run. In this case, though, companies have an extra opportunity. That’s because many of the same steps taken to comply with new reporting requirements—such as supply chain mapping—can also be used to drive decision-making. Such decisions will be informed by not only cost but also ESG impact at a core level to achieve the net-zero goals of the company. Many companies have already named their net-zero targets. With network-based capabilities, decision makers actually gain a line of sight to these targets and can tell very quickly if their ESG decisions will be effective.

If you’d like more information on Scope 3 and the role of a multi-enterprise supply chain business network in reporting and reducing emissions, please Contact Us. We’d love to talk with you.